[Landline] Steve Albini

...

On May 7, the same day Apple first transmitted its cruel and shocking commercial for the new iPad Pro—the one that shows, in loving and prolonged, sadistic detail, the mechanical crushing of creative tools and artifacts, analog expressions of human creativity and communication—Steve Albini, the outspoken musician, studio owner and engineer, devoted to what might loosely be called the old ways that work, died from a heart attack.

Correlation does not imply causation, of course, but sheesh.

Albini was 61. He had a staggering influence on underground music culture as an exponent of a certain approach to recording music, and as a working carrier of a kind of deep, reasoned ethicality—and learned wisdom—regarding how cultural life could be successfully conducted below the corporate showbiz line for the betterment of all.

He did not suffer foolishness—or fools—gladly, and his famously scabrous wit, combined with his university training in journalism, and what I gather was a voracious and wide-ranging reading habit, meant he was a better, more persuasive articulator of principle(s) in text, interview and conversation than almost any contemporary music “industry” participant at any station. Considering the feeble competition, that may be damning Albini by faint praise, but it should be remarked on.

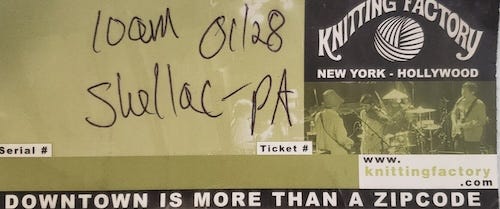

As much as I respected Albini, I never met the guy, never interviewed him. Just didn’t get around to it is my weak excuse. I saw him in performance only one time—a memorable Sunday brunch show with his band Shellac at the Knitting Factory in Los Angeles on January 28, 2002. Doors 10am; a box of complimentary Krispy Kreme donuts at every table in the bar; bright stage lights; abrasive, crooked, dynamic rock-ish music and good natured band-audience banter that built on the collective sugar high.

Over the last week I’ve tried to write something about the man appropriate to this awful moment…and I have failed. It’s too soon, he’s too big, and, frankly, why should I talk when there are so many others who are saying deeper things than I ever could. But I did a lot of looking around before I reached that conclusion. Here’s some of what I found1 that I thought might be of particular use, comfort, inspiration, or amusement.

An obituary by Marty Albini, posted to facebook:

Steve Albini entered this world on July 22nd, 1962 in Pasadena, CA. He left it by a heart attack May 7th, 2024. He leaves behind a grieving family and many friends and peers; this obituary will try to give the world an idea of the man we’re missing.

He was the youngest of three by Frank (at the time a grad student at Caltech) and Gina--high school sweethearts from the hardscrabble town of Madera, CA.

Steve played clarinet in grade school. Starting in high school in Missoula, MT, he gravitated toward the emerging punk rock genre, teaching himself the bass to play for the band Just Ducky. This obsession with music led to playing guitar and forming the band Big Black while he attended Northwestern University studying journalism.

His journalistic career also started in high school, writing record and concert reviews for the Hellgate Lance. These writings led to his first death threat. He would go on to write essays for various fanzines and music publications, including one called The Problem With Music detailing how musicians benefited very little from the business practices of the recording industry. Go read it. It’s epic.

Steve was fearless, willing to speak up about what he cared about and unconcerned about who took offense. This behavior did not always serve his commercial interests, but it gave him a reputation as a man of integrity who could not be bought or bullied in an industry that did a lot of both.

Following Big Black he formed the band Rapeman (named after a Japanese comic book and intended to be provocative, but a name he later regretted), and the band Shellac. Starting with his own bands and those of friends, he began to record as a sound engineer. This activity led to a studio in his home in Chicago, which eventually grew into Electrical Audio, a converted commercial building he turned into his dream studio. You can read about all the bands and projects he’s been associated with elsewhere; he’s not hard to find on the internet. It’s a long and storied list.

In 1996 he and his girlfriend (later wife) Heather Whinna began a simple project to help Chicago area families in need.2 They picked up letters that the post office collected from kids writing to Santa. The requests were for basic necessities, and they were moved to organize friends to donate what they could. They spent every Christmas thereafter delivering gifts to change the lives of the poorest of the poor. This effort grew into an annual 24 hour fundraiser at Second City, which is now a charity known as Letters to Santa, part of Poverty Alleviation Charities in Chicago.

All that activity is public, but Steve and Heather are responsible for countless other acts of private generosity. Without going into that list (you know who you are!) your stereotype of a punk rock musician probably doesn’t include the beloved uncle who barbecued for the weddings of his nieces and nephews. The devoted husband who stayed up late to cook for his wife. The studio owner who listed his cats as staff and went deep into debt to keep that staff employed during the pandemic. Host of many stray humans in need of a bed, a meal, a refuge from the cruelties of life.

Steve tended to obsess about various projects, master them, and move on. Among these were model rocketry, photography (he worked for a time retouching photos for an ad agency), cooking (he published a food blog, mariobatalivoice, for a time based on the meals he prepared for Heather), woodworking (he made some of the furnishings for the house he and Heather lived in), and of course poker. Steve won two bracelets at the World Series of Poker and hosted a regular game at his home.

Steve was also generous with his time, willing to talk to anyone wanting to follow in his footsteps as a musician or recording engineer. He gave lectures around the world and sat for many interviews, often patiently fielding the same questions but always with a thoughtful answer. His studio hosted many light-hearted but highly technical videos on the science and technology of sound recording and hosted numerous interns looking to learn his craft.

His family is drawing some comfort from the worldwide outpouring of support and affectionate remembrances. We’re glad we got to share him with you, and we urge you to go do something generous in his memory.

Steve is survived by his wife of 16 years, Heather Whinna; his mother, Gina; his brother Marty; sister Mona Goldbar; and numerous nieces and nephews who urge you to make a lot of noise in his honor.

From UniWatch by Paul Lukas, March 9, 2023:

Albini: I played Little League, I played Pony League, I played American Legion ball. I was always scrawny, so I played baseball up until my late teens, when everybody muscled up except me. I wanted to be a catcher, so I was constantly getting steamrollered. I would stay there in position, blocking the plate waiting for the throw, and I would just get creamed every game.

For a long time I used a hand-me-down 1950s catcher’s mitt that was my uncle’s. It was like this big, dumb sofa cushion of a catcher’s mitt. I eventually got my own mitt.

UW: What about your studio, Electrical Audio — do you have a company softball team or anything like that?

Albini: Chicago has an adult baseball league — the Chicago Metropolitan Baseball Association — that’s been around since the 1920s. So in 2003 we put a team together, called the Winnemac Electrons, “Winnemac” referring to Winnemac Park, where we played our home games. The team started as as Electrical employees and Electrical-adjacent kind of people. We were all in our 40s, with a lot of heavy smokers. It was sort of a drinking society of baseball enthusiasts, well past their prime, who were looking for a way to play baseball again. So that’s how the Electrons were born. The team still exists today, although I think only one of the original Electrons is still on the roster.

UW: Did you play?

Albini: I was only on the team for a couple of years. I didn’t play much because I’m bad. I’d basically be subbed in to play first base or something as a mercy, you know, out of pity. I don’t have any photos of me playing. I was kind of a mascot more than a player.

UW: Was there a ceremony for your number retirement, and do you have a framed No. 41 jersey hanging on a wall?

Albini [laughing]: No, no, nothing like that. The most formal thing that ever happened with the Electrons was, after we’d win a game, we’d go to a bar that was our regular hangout and I would pop for a round of wings.

…

UW: You wear your guitar strapped around your waist instead of over your shoulder. When and why did you start doing that?

Albini: I started my tenure as a musician by playing bass guitar in a punk band in Missoula, Montana. The gear available at the local family-run music store in town was a few terrible secondhand guitars and the new instruments they carried were the Peavey brand. So my first purchase, when I was 16 or 17, was a Peavey T-40 bass guitar.

Peavey made very workmanlike instruments — very proletarian, simple, heavy-duty, reliable. And anyone who’s ever picked up one of these things will recognize how insanely heavy they were. The guy who ran the company, Hartley Peavey, had this notion of sturdiness that he wanted his instruments to convey. And he instructed the people who were designing those instruments to make them heavy, so that when you picked it up, it felt substantial. The weight plays no part in the sound or the suitability of the instrument — it just makes it heavy. That’s the impression it’s supposed to make when you pick it up out of the stand — like, “Oh, this is heavy. This must be a serious instrument.”

Anyway, so I was wearing my Peavey T-40 bass guitar conventionally around my neck like everybody else does. But it was heavy and uncomfortable, and I hated it. So I started playing around with the strap and seeing if there was another way to wear it. I quickly came up with this idea of wrapping the guitar strap around my waist, and it immediately took the weight off of my shoulders. It also felt more natural because I have preposterously long limbs — truly ape-like limbs — so having the neck sticking straight out at a distance actually was more physically comfortable for me than having my arm bunched up against my body like I’d have to do if I wore the instrument conventionally. So everything about wearing it around my waist was instantly more comfortable and more natural, and I never looked back. I’ve always done it that way.

UW: Was it also fun to create an onstage look that was different from everyone else’s? Did that appeal to you?

Albini: It didn’t particularly matter to me that it was distinctive or unique.

UW: Really? I’m a little surprised to hear that.

Albini: It sounds dumb when I say this, because I do notice odd stylistic things, but I genuinely don’t care about style, at least for myself. I appreciate when other people have a good visual sense. But in my personal life, I don’t wear stylish clothes; I wear functional clothes. I don’t care about the style of my car. That sort of stuff doesn’t matter to me. I mean, look at me — I don’t try to project an image. I’m just a guy.

I care much more about the design of artifacts — things like record sleeves, flyers, stationery, books and magazines, stuff like that. The design of artifacts matters way more to me than me having a personal style.

From “I wanted it to be for keeps: an oral history of Shellac” by Emily Pothast (The Wire, 2024):

Steve Albini: When I first started playing publicly in the 80s — in 1978, 79, whenever – it never occurred to me for a moment that there would be reward, like financial reward, or that it would be a career. That was never even a ghost of an impression in my mind, that I would be a professional musician playing music for a living. Like that was not an ambition of mine, it didn’t seem realistic, and, like, in the circles that I’ve traveled in, those kinds of ambitions were seen as kind of gauche, or gaudy or unrealistic and delusional. Like, you’re in a band called The Fuckbabies, you think you’re gonna be on television? You know? It’s like, that kind of thinking just never entered our mind. And so you develop a pattern of behaviour and you develop a mode of thinking where none of that stuff is a consideration.

Now, if I had come of age in a later generation, where you could shoot yourself singing on your iPhone and post it on YouTube and be an international star, like if that was the reality I’m sure I would be an awful person by now, if I had come of age later where I didn’t have to make do with scraps and I didn’t have to just put things together on a shoestring. I’m sure that that would have played into my vanity and that I’d be awful. I feel like being formed in that scene tempered me as a person and made me rational and comfortable with less, is a way to describe it. And those scenes were all full of such freaks and weirdos, you know? Like having a guy in your band whose profession was that he was a weed dealer wasn’t a big deal. That was normal. Or having friends who were, like, part time prostitutes or whatever. Or having, you know, like people in the underground – like the real underground of society – all around you. That was normalised. And that also kind of tempered me as a person, made me more open minded about what kind of people are legitimate and what kind of people I should take seriously. I feel like all of that to me – that scene and those people formed me as a person. And I’m grateful for it. Because I know that I was susceptible to influence because they influenced me. And if I had fallen in with an uglier or dumber crowd, I would be a dumber and uglier person.

….

SA: Another concept that was kind of fundamental to [Shellac live peformance] from the beginning, which is that we’re all at the same show. The crowd, the bartenders, the people on stage, the guys working the show. We’re all at the same show. We’re all here having the same experience and we want everybody to participate in the thing as much as they can. And when you’re interacting with people that way, in a direct way, and an unfiltered way, then it kind of reinforces that you’re taking them seriously, that they’re a legitimate part of the show. They’re not just furniture that we’re extracting money from. They’re people having this experience with us. And, you know, I want to know what’s on their minds. And I really, really value getting these exchanges with the audience because it reinforces this thing that it’s not show business. We’re not just being paid to do labour in front of you. We’re not just extracting money from your appreciation of us. We’re having a thing. We’re all at the same gig, and we all get to participate in it. To me, that’s a pretty important part of it.

From “The Plumber: Steve Albini on Touch and Go, the Stooges, and how his analog work ethic is faring in the digital age” by Bob Mehr (Chicago Creader, 2006):

Steve Albini: When [Electrical Audio] started, everyone was rather adamant that you couldn’t do things the way we wanted to. That it would be impossible to run a record label without contracts or more professional accoutrements. Everyone said it would be impossible to run a recording studio that catered to a punk-rock client base because they don’t have any money and they’re not reliable, or whatever. I like the fact that Touch and Go and Electrical Audio have proven that all those people who thought they knew best were wrong. Not just that they were wrong to offer their opinion, but that they were wrong, period. It’s quite gratifying to realize you were smarter than all the people who were telling you you were gonna fail.

From “Bigger Black: 5 Easy Pieces w/Steve Albini” by Eugene S. Robinson (Feb. 2021):

[EUGENE:] I remember at some point you were doing this charity drive, a kind of local action that I had lots of respect for, but I'm more of the If the Roof Is On Fire Let the Motherfucker Burn school. Despite a reputation for cynicism that might confuse you, you were a superhero here it seems. What led to this?

STEVE: I met a good woman who started us both on a path of service. Heather Whinna runs Poverty Alleviation Charities (unconditionalgiving.org), which is an outgrowth of the two of us and some friends raising money and giving it to poor people on Christmas every year. It started out small, but by now she's given out several million dollars in direct aid to poor families, enough to change the trajectory of their lives. It seems obvious, but the solution for a family suffering poverty is to get them money. Not a tax credit, not a program, not something they need to qualify for or jump through hoops to access, just give them money. We've been doing it for more than 20 years now and it's not enough by any means, but it works.

…

[EUGENE:] Some folks who have gotten their tickets punched I begrudgingly still embrace for a variety of complicated reasons. Mike Tyson because he served his time, Paula Poundstone, David Letterman, and Quentin Tarantino? I somehow want to grant a pass. Louis CK, Elvis Costello, Woody Allen, and Roman Polanski I cannot. It's not willful...I just find myself much less interested in their work. Who is on your Keep/Toss list?

STEVE: I respect fighting as a trade less than you, so I was probably off the Tyson bandwagon before it got rolling. Anybody who uses a position of power, status or authority to exploit people who are vulnerable to that power, status or authority is dead to me. I don't care what kind of movies a rapist makes, don't care if other people think they're good, they're rapist movies and I'm not watching them. I have limited attention to lend to other people's art, and I get to choose who deserves it. I'll admit I laughed at Bill Cosby's humor before I knew what a monster he was. Never since. Those Spanish Fly jokes just hit different now.

I've never had a problem with transgressive art, but it sure seems like you can tell when it's just a veneer used to justify being a fucking creep. Always hated Vice, still hate it. Just a parade of gawkers reveling in whatever misery they can observe from an ironic distance. Fuck that shit completely.

Rogan, Barstool, all the anti-woke comics, just fuck them all in the eye. It's trash garbage and I want it all to fail. What if all the stupid shit your racist neighbor you can't stand said was typed up and put on a blog? Nope, still trash, still fuck it. I want them all out looking for work. Into the chipper with all of it.

From “‘He’d offset the intensity by setting his feet on fire’: PJ Harvey, Mogwai and more on Steve Albini,” a superb, devastating collection of remembrances from musicians who worked with Albini, gathered by Ben Beaumont-Thomas, Stevie Chick and Annie Zaleski (The Guardian, May 13, 2024):

Julie Cafritz of Pussy Galore: Jon [Spencer] and I were such incredibly devoted Big Black fans. That band was so powerful and sonically interesting. And so we weren’t thinking of, “Steve Albini, the recording studio engineer.” We were really drawn to him by the sheer talent that we saw in what we thought of as his main gig. I had a very strong, visceral impression, both of his guitar playing and his personality. It was so explosive. He was such a live wire. He was clearly bristling with intelligence. And, like Pussy Galore, really transgressive in that dumb, stupid way that young punk rockers were, when you want to take down society, so you say the most horrible thing.

When we arrived in Chicago to record with him, I was struck that he was a bundle of contradictions. But maybe that’s wrong – because maybe it’s just all the natural contradictions that somebody with such a strong personality and worldview and artistic sensibility has. Like all of this is part of the stew that is Steve Albini.

We met him at his domicile at the time, and he’s in the back yard, bleaching glass bottles, because he was about to embark on bottling his own root beer. Meticulously bleaching them – rinsing them, wiping them with a little cloth at the edge of his apron to keep the bleach off his already-bleached jeans, and then placing them in crates. And I was just like: “Oh my God. What a nerd!” [laughs] But the thing is, I was a nerd. I didn’t drink, I didn’t to drugs; he didn’t drink, he didn’t do drugs. And yet we had these outsize, really hardcore personalities.

He brought his intensity – that intensity of focus, that gaze, that meticulousness, that sort of doctrinaire way of being and approaching life – to every endeavour. You might think that somebody like that would not necessarily be the best collaborator in the studio. But it was really fun.

We recorded a song [Pussy Stomp from the album Right Now], and Jon wasn’t happy with the recording. But he was happy with the way it sounded when we played it in our van, which had much shittier speakers. We ran cables all the way out of the studio into the back alley, where Jon turned on the van, put the cassette in, and then blasted the music. And Steve recorded the sound of that track with two mics coming out of the stereo in the van. To me, that was everything a studio experience was supposed to be. It was creative, rigorously intellectual in its own way; it was fun. To me, that’s everything you need to know about Steve right there: really game and really excited by other people’s ideas.

He wisely grew out of a lot of the sort of dumb shit that we all do when we’re young. But then he replaced it with really smart shit. He was an extraordinary human being in terms of sheer intelligence and the power of how he would focus that. Everything was quick. And I knew him when it was all brutal. What’s interesting to me is that as he grew older and softer, he didn’t lose any of that edge. It just was put to better use.

Will Oldham: We’re experiencing an increasing momentum of things that run counter to seemingly anything that drove human civilisation forward. It seems like it’s kind of coming apart right now at a mind-boggling rate. It feels like Steve’s reward is not having to witness it, and our reward is getting to do our best to fill in the vacuum that his death leaves. He took on a lot of responsibility for everybody, so we didn’t have to think and do, because he was thinking and doing on our behalf. And I feel charged and prepared to move forward alongside Steve’s personal and professional legacy as much as possible. It’s hard for those of us for whom thoughtfulness is a principal virtue. There are few examples to look to, in the way Albini is.

From “Steve Albini Wants to Know Why His Carrots Look So Freaky” by Chris Crowley (Grub Street, July 2018):

Requiescat, Steve.

I also found this: four one-hour episodes of Albini as radio DJ/interviewer on NTS, made one year ago, that I’d never heard. I picked one episode at random this morning to listen to on a walk, which turned out to feature Albini in Terri Gross mode, interviewing Robert Rolfe Feddersen, the former singer of metal band Loudmouth, who is now a self-sufficient acoustic singer-songwriter permanently touring a circuit of microbreweries with his wife and dog. Absolutely fascinating. Dude wrote a theme song for the White Sox—which Albini recorded! Also on this episode: music by Scratch Acid, The Dicks, Glass Eye, Third World War, more.

“Why I Haven't Had a Conventional Christmas in 20 Years“ by Steve Albini (Huffington Post, 2015-6)

I've been devouring Albini stuff this week, constantly. I don't think I've ever seen such an outpouring of love for an artist, just day after day of it, and I read it all. But what I've really loved, as much as seeing so many of Albini's own collected words in interviews and articles, are the tributes from so many people he's touched -- bands he's recorded and eaten meals with, colleagues in the recording biz, etc. For one thing, musicians are really good writers! I've been moved to tears by guitarists describing his miking techniques, and folks who worked for him describing gifts he's given them. Such a void he leaves. Requiescat, Steve.

Thanks Jay